T.J. is correct in his assessment of the new album by Bobby Sanabria. It is stunning. He and I may differ on which songs may be our favorites but we are both excited at the results of the music. But allow me to get right to it.

The first track is entitled The French Connection and is indeed the theme from the 1972 movie of the same name but this is not what was heard on Don Ellis’ record Connection released in that year.

The song opens with a terrific percussion introduction of drums, palmas, congas and more accompanied by trumpeter Chris Washburne on dijeridoo. The intro is captivating enough of its own accord but then the horn section of Danny Rivera, Shareef Clayton and Jeff Lederer join in at 0:34 with an understated but pulsating addition.

It is arranged so very well. I always admired the original Ellis composition but that was a movie theme and Danny Rivera and Bobby Sanabria have transformed it into a brilliant jazz short suite of three all-too-brief movements. The horn introduction and development gives way to Enrique Haneine’s inspired piano solo that reminds the listener of Cecil Taylor’s most sublime moments. The short piano solo then surrenders to a more big band sound with the return of the horn and rhythm sections. Jeff Lederer’s tenor sax scorches the third movement while Sanabria lays down beautiful percussion with added xylophone textures.

Bobby Sanabria was at the eye of the storm during the Grammy Awards debacle wherein the Grammy chairman Neil Portnow had dropped 31 categories from 2012 Grammy contention. Included in those lost categories was the Best Latin Jazz category. In no small measure, musicians Bobby Sanabria, Bobby Matos, John Santos, and Oscar Hernandez, along with publicist Sarah Bisconte, had managed to raise enough public outcries that, at least, the Best Latin Jazz category was reinstated for the 2013 Grammy Awards.

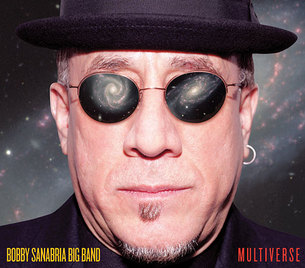

That said, Multiverse should not only contend for that category but for Best Jazz Album of the Year, as well. This recording has taken all the great elements of the Latin Jazz universe and has fused with so many other genres to truly create a multiverse of musical dimensions. In the first track alone, the easily recognizable Latin rhythms were joined by Big Band, Free Jazz, and Fusion stylings. Folklorist Elena Martinez gives insightful and analytical description of it in her liner notes of the CD. Also included in the liner is a telling quotation from Octavio Paz from 1970. “Life is plurality, death is uniformity.”

Such is Bobby Sanabria’s Mulitiverse. The plurality is invigorating and life-affirming.

Below is a YouTube video of Bobby's Big Band at the Lincoln Center in 2010.

Jeremy Fletcher arranged Cachita but he composed Jump Shot which followed. It is well-conceived and well-executed by all the players. Although it may have New York City in mind, it certainly takes me back to my Miami days of enjoying the Cuban bands in the great clubs there. The composition allows a cool solo on bass trombone by Chris Washburne followed by Lederer again on tenor sax. The rhythm section is held down steadily throughout the number with the macho guiro, which allows for departures for the drums while the guiro anchors the beat.

With that in mind, Norbert Stachel opens the tune with a sweet flute intro. The structure of Andrew Neesley’s arrangement begins to take shape and is developed by David Miller, Jonathan Barnes and Shareef Clayton on the horns. The melody begins to emerge and becomes identifiable before the lovely voice of Chareneè Wade leaves no doubt that it is indeed Harold Arlen’s Over the Rainbow. The song has been covered, after Judy Garland’s original, by everyone from Patti LaBelle to Willie Nelson. Probably most famous in recent memory is the version by Israel Kamakawiwo'ole. Each and every version to date has left me saddened, almost mournful, at what life leaves short in us. It has been rendered as a hope for escape from present life.

This is not what Bobby Sanabria brings to the hearer in his version. The intro is wistful without being sad. Under Ms. Wade’s heart-felt treatment, we are left with the feeling that home is the place over the rainbow. That place is where we already find ourselves, if only we recognize it. “Why can’t I?” has lost its despair and becomes a question of self-imposed limitations. It becomes a question of “What is stopping me?” The middle cha-cha section is deliciously uplifting and joyful. Ms. Wade drives home the point when the music has faded. She states simply “There’s no place like home.” Please allow for a bold statement but Bobby and Ms. Wade are the first to get it right. Ever.

Andrew Neesley, then, is the composer of Que Viva Candido and the song begins with an electrifying horn intro that opens slightly for a very jazzy piano contribution before returning to the powerful horns. Throughout, however, Enrique Haneine maintains the coolest piano support before getting more moments of lead.

The song breaks up into classic Latin segments that are so uniquely informed by Bobby’s South Bronx upbringing. It is almost as if one can imagine standing on the street and listening to various musical genres coming from an open window there, a passing car here, a kid with a radio close by, an impromptu vocal group on the street corner… the different styles weave in and out, coalesce, then break apart again. All the while Maestro Sanabria maintains tight cohesion and the percussive drive throughout this and every piece.

Trombonist Chris Washburne wrote Wordsworth Ho! and the blistering horn corps passages provide spotlight set-ups for the delicate sax solos of Peter Brainin and the bold trombone solos of Washburne himself. In fact, the sax solo from 2:10 to 2:47 was especially moving with the melodic line emboldened by Washburne’s solo. The return to the horn corps provided the nice platform from which to close. The piece fades out with the sounds of Washburne’s open embouchure buzzing. Cool end.

Wayne Shorter is a divinity in the jazz world and his piece Speak No Evil is a testament to this. Jeff Lederer arranged the piece for Bobby’s Big Band and it works. Hard. Peter Brainin gets the sax solo nod again and I find myself enthralled again; enthralled by the La Bruja rap that underscores it. It is an intriguing switch the let the sax continue overtop as the vocal hugs the subfloor. But make no mistake—it is a very righteous rap. All this leads to Bobby’s lighting up the bongos on a solo of his own. The horns carry the end and conclude with staccato pulses that then fade off leaving Bobby’s bongos in the wake.

Broken Heart (composed by the revered Eugene Marlow) reveals just that; a broken heart that has learned to survive and revive. Under Bobby’s treatment, laments of brokenness and despair are transformed into hymns of thanksgiving and rejoicing. The David DeJesus soprano sax solo is fondly reminiscent of later Coltrane while the punch and drive of the percussion maintain the festival current. The macho guiro provides the heartbeat while the horns reveal the climb from brokenness to beatitude.

The final two pieces on Multiverse also reveal Bobby Sanabria to be a man who gives honor and respect. Both pieces are lessons in jazz history. The first is entitled Afro-Cuban Jazz Suite for Duke Ellington (Michael Philip Mossman, Composer). An homage to one of jazz’ greatest composers and band leaders, the music of Ellington can be heard threading in and out for the entirety of the almost 14 minute piece. The song is upheld throughout by the Afro-Cuban rhythms of Sanabria and company.

This is the track that allows for so much room for the percussion to explore those unique rhythms that set Latin Jazz apart from so much else in the music world. Bobby absolutely set the place ablaze with the rapid-fire percussion of brilliant runs and syncopated patterns. He has been called the heir of Tito Puente but this is to lose sight of Bobby Sanabria’s unique voice and message. He celebrates the giants of the past without being strangled by them.

That lesson in historical appreciation continues and is brought to fulfillment in the final track The Chicken/From Havana to Harlem—100 Years of Mario Bauza. Mario Bauza was born in Cuba in 1911 and the track celebrates the 100 years since Bauza’s birth. Bauza came to New York City in 1925 and joined Antonio Romeau’s band at the age of fourteen. He was hired for Chick Webb’s orchestra and became fast friends with Dizzy Gillespie and even brought Ella Fitzgerald into Webb’s group. He later moved on to Cab Calloway’s band before joining his brother-in-law’s band Machito and his Afro Cubans. In the early 1940’s, Bauza would bring a young Tito Puente into Machito’s band.

While musical director for Machito, Mario Bauza composed Tanga a song which began as a “descarga” or Cuban improvisation. Later, Bauza made more complex arrangements for Tanga and it became the first true Afro-Cuban jazz piece. It can rightly be stated that Bauza invented the Afro-Cuban jazz genre.

This track celebrates Bauza and the birth of such a remarkable and uplifting category of music.

The spoken lines to open the track are “Rejoice, brothers and sisters, for America’s greatest art-form, for anyplace where jazz is played is a sacred place. So thank you for coming to church! A-men…and a-women, too…” The lines are brilliantly traded between a male and a female speaker in a soulful call-and-response arrangement that is enough to make one ready for an altar-call. During the rap, Shareef Clayton is sounding like the angel Gabriel calling the faithful home.

The hot introduction makes way for the smoking development of the piece. The corps progression of the horns is soul-infused jazz that is affectionately complimentary to the Afro-Cuban rhythms played alongside and underneath. Norbert Stachel’s tenor sax is a grand blast to the celebration going on. The music surrenders to Bobby’s drums and La Bruja’s rap.

That rap is the history lesson par excellence. The Apollo Theater is proclaimed as the place in the heart of Harlem that connected jazz lovers to the beginnings of the music in Africa. She gives a rap instruction on the roots of the talking drum, mambo and the relief that they brought. “And where there was unrest/ there was always music to reverse the stress,” she intones. Mentions of Chick Webb, Cab Calloway and Fletcher Henderson abound and then comes the great line, “And let us not forget the Holy Trinity, the Three Kings; Machito, Tito Puente, y Tito Rodriquez.” Names familiar and not-so-familiar are recited; Sammy Davis, Jr., Desi Arnaz, Rafael Hernandez … “It was a magical era, a time in musical history that can never be equated or duplicated, only celebrated and venerated.”

Indeed, the Bobby Sanabria Big Band has celebrated and venerated the past and present of jazz. From Ellington to Bauza, Bobby has instructed us on our musical heritage and has given great reason to revel in what has been offered to us in the last 100 years. But Bobby has not stopped there. Instead, his drum propels us forward into furthering the expressions of art and life that will hopefully indeed “reverse the stress.”

The music and message of Multiverse is powerful—plurality is life. Bobby Sanabria is a prophet of life.

To hear more of the message in samples or to download or purchase the CD, go to www.jazzheads.com.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed