The crew of the doomed B-29 Marauder.

The crew of the doomed B-29 Marauder. The Germans had launched their last assault through the Ardennes Forest and had created a salient or “bulge” in the Allied lines, thus the name of the campaign. That was launched on December 16, 1944.

Months before, six airmen from Wisconsin and Illinois had been assembled as a crew for a Martin B-26 “Marauder.” Included in the crew were radioman and waist-gunner Corporal Edward L. Potocnik of Owen and engineer and waist-gunner Private Joseph W. Kowalski from Illinois.

They were part of the 391st bomber group and departed Maine for the European Theater of Operations August 17, 1944. After stops in Labrador, Greenland, Iceland and Ireland they finally flew their B-26 to their new base in Roy Arhmede, France on October 1 whence they would fly missions against German targets along the Mosel River.

After five recorded bombing missions, the 574th bomber squadron of the 391st bomber group was ordered into the Battle of the Bulge with the primary target of the railway bridge at Ahrweiler near Eifel, Germany. This was a key factor in the German supply line for the Ardennes front. Both sides knew the value of the target.

There were thirty Allied planes in the raid. Fourteen made it back to base.

The German air defense strategy was effectively simple: anti-aircraft (“flak”) guns would rake the fuselage and engines of the Allied aircraft from the ground, thus “softening them up” for the fighter pilots of the German Luftwaffe. In this raid, in particular, it was terrifyingly efficient. Adding to the chaos in the air, an unusually large fighter group—numbering sixty—jumped the wounded 574th squadron.

Edward Potocnik

Edward Potocnik As a result, Kowalski was injured and losing blood so rapidly that he could not don his own parachute. In addition, if the plane were to return to base, Kowalski could not survive the flight. Potocnik buckled on Kowalski’s parachute and pushed him from the waist window at 8,000 feet.

The B-26 was then hit by enemy aircraft fire as a mixed group of Me-109’s and FW-190’s who caught the bomber group by surprise, coming out of the sun.

According to Potocnik, all of the remaining crew were in their positions but the plane had taken far too much damage to survive. The pilot, Lt. Dale Detjens of Wausau, tried to maintain control of the plane and would not leave his seat.

It should be remembered that when a plane is going down and spins out of control, gravitational forces (G-force) increase due to effects of centrifugal force. It becomes impossible to move as the g-force increases. Potocnik knew that his time to act was limited.

As Potocnik and tail-gunner Staff-sergeant Joseph J. Miller were trying to make it to the waist window. Again Potocnik recalls, Miller “who was not wounded, tried to come to the waist to bail out but didn’t get to the window in time when the plane suddenly went out of control. I looked down at the tail-gunner and made eye contact with him, and we both knew that I was going to survive and he would not. We both knew that he would not make it to the waist in time to bail out because of the G-force of the plane. The image of his eyes is, and has always been, forever imprinted in my mind. That image is what I have always carried with me throughout my life.”

In what must have seemed an eternity, Potocnik jumped from the plane only 30 seconds after he had pushed Kowalski out. He barely had time to open the parachute before he was on the ground.

“I landed so close to the plane,” he remembered, “that the explosion and concussion of the plane helped slow the speed of my fall.” The B-26 hit the ground 200 yards west of a farm and went nose-first into a wetland cow pasture, near the small hamlet of Bauler.

In a field, an eleven year old German boy watched the plane go down.

When Edward Potocnik’s parachute settled, he was immediately surrounded by a group of young German boys, probably the Hitler Youth, who had only one weapon between them. They had been told to keep watch and to capture any enemy fliers or soldiers.

What Potocnik could not have known was that Joe Kowalski, the wounded waist-gunner whose life Potocnik had saved, was also taken prisoner by a lone German soldier where Kowalski came to earth. The soldier took him to the nearby village of Bauler where his wounds could be tended quickly.

Earlier in the war, Luise Vetter moved her family out of the city of Dusseldorf which was suffering from the heavy and repeated bombing from the British and Americans. Her daughter had become a nurse and was away working at a hospital in Adenau, Germany. Frau Vetter had moved her family to the old family hunting cottage at Bauler.

When Kowalski was taken to Bauler, villagers took him to the home of the only woman in the village who could speak English, Luise Vetter. In her diary, Frau Vetter said that she “first soothed him, then dressed his wounds while he lay on our kitchen table which was under the Advent wreath the family had made from berries and vines from the garden.”

She recalled looking down and thinking “this boy is some mother’s son.” Instead of seeing him as an enemy soldier, she saw him as a son. That day, Luise Vetter reached beyond nationality and into humanity.

| The following poem is a re-interpretation in English of the original German language poem by Luise Vetter of Bauler, District of Ahrweiler, Germany. Before me, the enemy, wounded lies Mid agony, pleading, still he defies. The sky gave forth a deafening drone As human targets fell to the snow. Before me, the enemy, wounded lies His plight’s solution, time defies. The enemy, helpless, cries and pleads My heart for my homeland weeps and bleeds. O’er stripes and stars, blood freely flows My hand, reluctant reached, then froze. Is this not another mother’s son Are his wounds less, his needs undone? Oh fear, oh death, oh horrors of war When will this misery at last be o’er? What end to see this hatred cease And in its place, eternal peace? Compassion’s foe, no longer blind The victor’s spoils now re-defined. May the secret of war this simple truth impart That the surest target is a mother’s heart! |

Eddie Potocnik was taken by his captors to a Prisoner-of-War (POW) camp. He was given a small tin for his rations and each prisoner was given additional rations of cigarettes and chocolate. Potocnik claimed that he was kept alive by not smoking. He would trade his rations of cigarettes for chocolates which gave him needed calories. Instead of sleeping on cots in the POW barracks, Potocnik would sleep in slit-trenches outdoors to avoid the dangers of bombing.

Shortly after the events of December, 1944, Luise Vetter wrote a poem describing her experience with the wounded airman. It is a telling description of doubt in the face of an enemy that is overcome by human compassion.

The war in Europe ended May 8, 1945. It was Eddie’s birthday.

Potocnik and Kowalski made it back to the United States. Kowalski was sent to a Chicago hospital where a finger was amputated and he suffered pains in his leg. Potocnik suffered from shrapnel wounds that caused him great distress. Their four crewmates were buried in Germany.

Eddie came back to Owen-Withee where he married Berniece in 1947 and raised turkeys. Joe married and moved to California.

Planning a trip to see Joe in the early 1952, Eddie and Berniece Potocnik were preparing for their trip when they received a call from Joe’s wife. They were told not to come. Joe Kowalski had died.

Three Wisconsin travelers fulfilled the quest, as far as was possible. Dale and Kathy Bartz with Rosemary Berchem had traveled to Germany where they met Arnhild Wöste who introduced them to Hermann Bierschbach. Herr Bierschbach passed the poem on to the three travelers who, with Frau Wöste’s help, translated the poem into English.

Eddie Kowalski was long dead and he left no heirs. They did, however, find Eddie Potocnik. They were able to meet with Eddie and Berniece and bring the poem to the United States—a poem of great beauty and compassion.

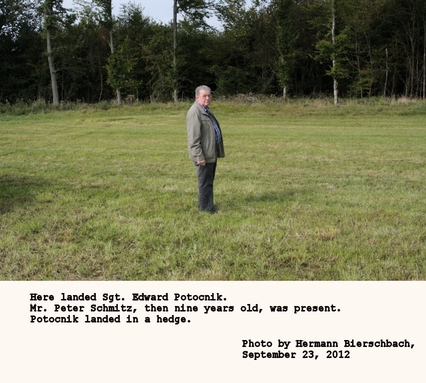

| A letter from Germany The following letter was sent to & Mrs. Edward Potocnik from the translator in Germany Dear Mr. and Mrs. Potocnik, It means a lot to me to write this letter to you today but let me introduce myself first. My name is Arnhild Wöste. You may have heard of me by my American friends Rosemary Berchem and Kathy and Dale Bartz who visited with you last year. Together we had done a trip to the area where you, Mr. Potocnik, crashed with a warplane on December 23, 1944. During our visit we learned about you, Mr. Joseph Kowalski and the other members of the crew who unfortunately didn’t survive. Your terrible fate moved us very much when Hermann Bierschbach, the elderly man pictured in the newspaper article, told us about it and showed to us the photos and the documents he had collected. The villagers never forgot about the tragedy of December 23, 1944, and they still talk about it today. Please know that people here in Germany are very grateful for what you Americans have done for us and our country. We are aware that our situation would be very poor and bad if you and others wouldn’t have risked and | often even given your lives to free Germany. We are trying hard to keep these memories alive with the young ones. I’m a teacher of history myself. Thus, this newspaper article attracted a lot attention. People got in touch with Hermann Bierschbach, the journalist and the newspaper to thank them for the information and to let them know how much they had been moved by it. Hermann Bierschbach gave me the photos that show the place where you landed with your parachute. Peter Schmitz, who, at the age of nine, witnessed the scene, showed the exact spot. It’s my hope that your fate and the tragedy of December 23, 1944, together with the poem, will help to make people aware that we are all brothers and sisters and how terrible wars are. I have experienced that it does work – and not only in Eifel area but also further north where I live. My students were very touched when I told them about you, Mr. Joseph Kowalski, the other crew members and the poem. Thank you for risking your life and bearing the horrors of war in order to save Germany. Herman Bierschbach and other people in Eifel area asked me to send you their greetings, thanks and best wishes. Wishing you and your family all the best, Arnhild Wöste |

All but one of the B-26 crewmates are gone. Luise and Freya Vetter have passed, as well. On opposite sides of the Atlantic, Hermann Bierschbach and Eddie Potocnik sit and remember December 23, 1944 and a plane falling from the sky/

He didn't know me and couldn't communicate but I just had to spend some time with him. When a writer devotes so much time to the research and writing of someone's story, a bond develops. His passing leaves me grieved but grateful that I got to tell a small part of his story.

On the evening before his funeral service, I got to meet with some of Eddie's family. What lovely and charming people. Berniece is a adorable now as when Eddie married her. The family is absolutely charming.

In that small town in Germany, there is a small shrine dedicated to the events described above. I am honored to report that this article is a part of that display.

God bless you, dear Eddie.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed