He has performed with Stevie Wonder, Wyclef Jean and the Jimmy Heath Big Band and is competent and compatible with those and various other artists from Snarky Puppy to Don Byron and Linda Oh. The man is comfortable in his own world and opens the gates for the willing to join him.

His track selection proves his open-mindedness and skill as he moves from J.S. Bach to Coltrane to Webern to Outkast with amazing lightness and integrity. I say integrity because he does no violence to the original compositions in his arrangements while—at the same time—recasting them with varied lights and shades.

He breaks up, for example, the four movements of Bach’s Solo Violin Sonata in G minor (BWV 1001) across the space of the album and rearranges the movements to fit and sit in complement to the pieces that surround them. He does the same with Anton Webern’s Four Pieces for Violin and Piano, op.7. The original pieces work splendidly with the arrangements. This results in a special fluidity in the progress of the music.

As I said, incredible scope and depth.

With Stewart and his violin are Alex Hills on piano, Alex Wyatt on percussion, Tyler Gilmore on electronics and Fung Chen Hwei on 2nd violin (track 22), Joanna Mattrey on viola (tracks 20, 22) and Jeremy Harman on cello (tracks 14, 22).

The album opens with the Adagio from Bach’s Solo Violin Sonata in G minor. This is the only one of the four movements that remains in Bach’s order. Originally, the order of movements were Adagio-Fugue (Allegro)-Siciliana-Presto. For Stewart, Adagio-Presto-Siciliana-Fugue works better…and he’s correct.

The Adagio is attacked with dedication and warmth. Be silent, Georges Enescu, you old ghost. A living spirit among us has something to say.

Just after the one-minute mark, the two Alexes join in on keyboards and percussion and this album has just taken a brilliant turn. This is not the cheesy “Turned on Bach” from the 1970s. This has got soul and swing.

From one master to another, the second track is John Coltrane’s Giant Steps. The violin of Curtis Stewart carries the voice of Coltrane’s saxophone and the outcome is fascinating. The arrangement is as cool as Coltrane could ever ask and the musicians deliver.

With every track, a written meditation and/or quote accompanies the music. The Unfolding parchment of the packaging is a companion work of creativity that should be enjoyed alongside, not in addition to or instead of, the music it elucidates. I recommend enjoying it simultaneously. And learning from the experience.

A Color Between Colors from Webern follows after. The piece is only 59 seconds in duration but the depth achieved so quickly is profound. The written pieces contrast Gauguin and—of all people—Adolf Hitler. Experience for yourself the effect.

Stewart’s original piece, Alone Together, follows. There is a sweetness in this Grappelli-esque work, a charm that captivates and enriches.

Anton Webern’s Four Pieces for Violin and Piano, op.7 makes its first appearance next with the first of the four pieces. The piece is an exercise in subdued dynamics and percussion. The dialogue of melodic fragments and rhythmic currents compels attention.

Like with the Bach sonata, Stewart will break up the progression by rearranging the pieces in 1-3-4-2 order. There is a reason, of course.

Webern arranged his four to show contrasts in tempo and dynamic character. The even numbered pieces were both to be slow and subdued while the odd numbered pieces were to be fully dynamic and rapid.

Stewart’s arrangement of both the pieces and their order, creates an ever-brightening and more vibrant hue. He is clever. I mean that in a good way.

After the first of Weberns comes another of the Webern-inspired works entitled Contrast Color. Another very short interlude at only 41 seconds which serves to separate the Webern from what follows after.

Indeed, what follows after is an arrangement of Outkast’s Prototype. It opens with a melancholy intonation that moves ever-so-sweetly into a funkier bit of affection. It is whimsical and delightful. Not as apparently serious as other tracks, this dedication to melody contains the hope of sustained love or, at least, the prototype of it. Beautiful work.

The Presto of Bach’s Sonata in G minor is, of course, lively and quick. The shimmering colors of the Presto are on sonic display in full exposure. Alex Wyatt’s percussion gets special attention.

Of Webern: Compare gives another interlude between the quick and the slow as it serves to bridge between the Presto and the third of Webern’s Four Pieces. As with the first of the four, it is in the slower tempo with the undeveloped dynamics.

A whole section of original compositions comes next with four works from Curtis Stewart himself prefaced by one from Alex Hills.

Hills’ Prime is a cool mover with fascinating tempo switches and tight melodic movement. Wyatt again turns in a brilliant bit of rhythm before morphing into Stewart’s Descent which causes Hills’ electric piano and Stewart’s violin to regale the listener with a tale of love and regret and emptiness.

Tectonics by Curtis Stewart moves as slowly as the Earth’s plates in the opening (Okay, not really) but that motion shifts creates a beauty of movement as surely as the Indian subcontinent colliding with the main plate of Asia to create the Himalayas. The colorful ‘scapes and scenes are resplendent with shade and tones that only the ear can see. This could be my favorite piece on the album…including the Bach.

Stewart’s A Breath in Time is performed by Jeremy Harman on cello. It is slow, evocative and meaningful with its references to inner power.

The originals section—in fact, the Of Color(s) section—concludes with Stewart’s Gone. It is forlorn and reminiscent. It is call for what is no longer present. A person. A place. An emotion. A thought.

The (UN)-folding section opens with the Siciliana of Bach’s Sonata. The pizzicato of the violin is taken over by the electronics of Tyler Gilmore before Stewart resumes the dominance. Gilmore creates a rhythmic substructure that is in stark but brilliant contrast to the melodic lines.

The Siciliana is immediately followed by the Fugue of the Sonata. Stewart labels this as a Tyler Gilmore Remix. The electronica warps and weaves the melodic lines into something blurred and incredibly intriguing.

Webern’s fourth of the Four Pieces is, along with the second which follows, more dynamic and awash with watercolor imagery. The electronics of the second is a fine touch of texture.

Stewart’s A Drop of Wind is a more lyrical work against the stark backdrop as Stewart contrasts with Joanna Mattrey’s viola.

The penultimate tracks are Of Color(s) and UN-folding Remix by Tyler Gilmore followed by Of Color(s) and UN-folding by Curtis Stewart. The Remix coming before the original mix. However, I appreciate the electronics-laden remix first. It allows for a movement away from the harsh effects to the lusher strings of Stewart’s and Hwei’s violins, Mattrey’s viola and Harman’s cello. The twin tracks create a contrast in tone and hue that is unmistakable.

The album concludes with a reprise of Gone. A lovely, lonely farewell.

In the liner notes, one of the most telling quotes is from Shel Silverstein. “And all the colors I am inside have not been invented yet.”

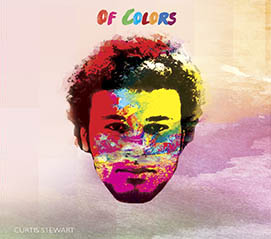

This is the strength and the beauty and the wonder of Curtis Stewart’s Of Color(s) and UN-folding, that in expressing vivid musical colors, in sharing the poetry of his own composing, in remembering the words of those who have imagined before, he shows his audience the colors inside of himself—color(s) not yet invented.

Far from self-indulgent, it is self-revelatory. It is vulnerable. It is creation.

~Travis Rogers, Jr. is The Jazz Owl

RSS Feed

RSS Feed