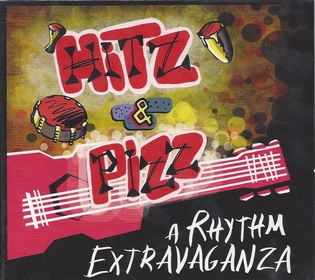

“Hitz & Pizz; a Rhythm Extravaganza” is a 2011 CD release culled from three of Marlow’s previous CD's entitled “Wonderful Discovery” (MEII Enterprises, 2007), “Celebrations” (MEII Enterprises, 2010) and “A Fresh Take” (MEII Enterprises, 2011). Don’t be misled; this is not a greatest hits collection or a tribute. This is something extraordinary.

The tracks included here are great representatives of the various and varying rhythmic patterns found in Latin, Afro-Cuban, Brazilian and Funk styles. On the fifteen tracks, he has some of the finest rhythm section musicians to be found anywhere.

The album opens as the title of the first track designates--Fast & Furious. It is focused on the hard bop rhythm patterns that Marlow describes as “still using the rhythmic parameters set by swing.”

Hard bop developed as a logical but bold extension of bebop music. It was logical in the sense of the inevitability of it being infused with the newly-emerging energy of rock and roll. It was bold for the same reason because jazz purists often saw little room for fusion of any kind.

The term began to appear in jazz literature in the mid-1950’s to speak of a new movement within jazz which brought together influences from gospel, blues and R&B. It usually referenced the playing of saxophone and piano but soon that hard bop groove become distinct and unmistakable.

In his book Hard Bop, David Rosenthal posits that the sub-genre grew out of the hearts and minds of young African-American musicians who had grown up when bop and R&B were the most popular forms of African-American music. The most recognized names from that group were none other than Miles Davis and Cannonball Adderly.

Bobby Sanabria points out that “hard bop in the 1960′s developed an intense aggressive approach characterized by drummers like Elvin Jones and Tony Williams who added the power of rock to the vocabulary of jazz.” This, of course, is true but the sound first developed in the mid-1950's with Art Blakely laying down the first hard bop groove.

Whether or not hard bop was a response to the cool jazz of California or the bebop of New York, it was greatly supported by Blue Note Records and that gave it instant credibility for some. Even though there were other expressions of jazz that developed in the '60’s, one can still hear that hard groove being recorded and performed today, as demonstrated on this track from Hitz & Pizz.

Here, Bobby Sanabria on drums, Cristian Rivera on congas and Frank Wagner on bass turn in a brilliant example of this rhythmic style. What became immediately clear in listening to this track was that I was going to be revisiting all three of Eugene Marlow's previous CD's to hear the rhythms again with the music of piano and horns included. To hear the rhythm section alone truly gives an appreciation of the structure upon which the melodies are built.

Musicologists love to label things and the labels can be too exacting when referencing cultures that did not apply or even appreciate such hard and fast distinction. Too often the lines of demarcation between this style and that are only a hair’s breadth and can become unusable when speaking of musical styles that were often dependent on what hollow piece of construction debris was im- mediately available to be used to create the rhythm. Xicá employed three barrel drums, a large maraca and two sticks being struck on an empty whiskey barrel laid on its side. In a later track, even a metal hoe-blade makes an appearance!

The cultures that used steel drums of varying sized and densities, whiskey barrels and goatskin-covered barrels and whatever else depending on what was available, cannot or chooses not to understand the fixation on categories from those whose tympanis always looked and sounded the same. What is the point, they must ask, in assigning such standards?

Not only were the instruments and rhythms defiant of category but the names of particular rhythmic patterns were different from one village or region to the next. This is true of the bomba rhythm which developed in Puerto Rico. There are many bomba rhythms such as Holandes, Xicá, Yuba, Gracima, Seis Corrido, Corvé, Cuembé, Leró, Calindá, Belé and more.

At its heart, bomba is a partnership or perhaps a competition between percussionsists, dancers and singers; it is a true community endeavor and became wildly popular with the dance orchestras. Usually, there are five players but this track has been adapted for just Bobby Sanabria on drums and Christian Rivera again on congas. The conversation between Sanabria and Rivera is absolutely captivating. Eugene Marlow points out the pitch bending played by Sanabria on the drums as he intones the vocabulary of the three barrel drums. Astonishing is the only word to describe what is heard on this track.

Free Range Bass a la Rumba is the third selection. Rumba is an entire family of rhythms, songs and dances which began in Cuba as a marriage of the musical traditions of Africa brought to Cuba by the slave ships and that of the Spanish colonizers. The name comes from the Cuban-Spanish word rumbo meaning "party" and the term rumba first began to spread in the late 1930’s. The term, however, soon developed into a somewhat catch-all phrase.

Afro-Cuban rumba is centered around a five-stroke pattern that gives it a form structure that makes it almost impossible to misidentify. Cuban Rumba can be categorized into three basic types: Yambú, Columbia, and Guaguancó. Yambú is the oldest and slowest of the styles. The most popular style is Havana-born Guaguancó.

This is the form that features three congas ranging from largest to smallest, and two sticks striking any wooden surface, as well as claves. It creates a highly interactive play between musicians, vocalists and dancers. Guaguancó is also a couple’s dance that is a symbolic game of sexually-charged flirtation.

The claves are two sticks that are struck together but the word clave also indicates the rhythm that is usually produced by the claves themselves. The Spanish word clave means “key.”

And clave has been called the key to Afro-Cuban music. The clave is a two bar pattern which sets the foundation for this style of music. These patterns can be played in two different directions. Either the 2-3 direction or the 3-2 direction. This simply means that in the first bar there are two notes being played, and three notes being played in the second bar. Or the opposite, three notes in the first bar, and two notes in the second bar.

The dance is a good-humored portrayal of the male trying to catch his partner with a single pelvic thrust. This move is called the vacuano or "injection." Sometimes the same move is performed by manipulation of the hand or foot. The female holds onto the ends of her skirt while moving her upper and lower body in opposite motions. She opens and closes her skirt in time with the music.

Bembe’ Madness is based on the Bembe’ beat brought to Cuba by the Yorubas of Nigeria. This word actually comes from the African word bembes and these were religious feasts with dancing, drumming, and singing. The Bembe’ groove is an Afro-Cuban beat played in 6/8, originally with a mix of four drums, bongos, djembes, and beaded gourds or shakeres. A bell marked the time accompanied by the three shakeres. The bell pattern was the basic groove that could be played at slower or faster tempos.

There is much theology behind the beat because the feasts celebrated here were in respect of the Orishas or deities of the Yoruba people. This theology was based upon the veneration of over a thousand nature gods and goddesses which represented all of the forces of nature. One god in particular, Olodumare, was the supreme deity of the Yorubas. After being brought in slavery to the New World (Cuba and Brazil, most notably), the Yorubas established a pantheon of 22 deities and these were named in correspondence with the deities and saints of Catholicism. Cleverly hiding their gods/goddesses among the Catholic saints, they avoided persecution and gave raise to what is today called Santeria or Saint Worship.

The whole pattern was adapted again to drums and congas. This piece is fiercely complex and it sounds as if the bell pattern is translated from cymbals to cowbell to rim shots. To add to the highly demanding piece, a bridge was inserted with the Venezuelan Joropo beat. This is a 3/4 transition and it is intimidating.

Again, however, Sanabria and Rivera are exactly the percussionists for the job. They flawlessly catch the hearer into an ecstatic state that has little or nothing to do with religion but with the celebration of being human and being alive.

A Mixed Boogaloo Bag follows next. Boogaloo or Bugalú was also called the Shing-a-ling and refers to R&B or “anything with a backbeat that was funky,” according to Eugene Marlow. It was popular among African-American Southerners in the 1960’s.

However, the Boogaloo form began in New York City among teenage Cubans and Puerto Ricans. The style was a fusion of popular African-American R&B and Soul, with Mambo and Son Montuno. Interestingly, Middle Eastern rhythms are also fused into this track with Sanabria, Rivera and Wagner again.

Boogaloo has been called "the first Nuyorican music" and Izzy Sanabria called it "the greatest potential that Cuban rhythms had to really cross over in terms of music." All of this transpired when Mongo Santamaria added Afro-Cuban rhythms to Herbie Hancock’s “Watermelon Man.”

Use of the term boogaloo as a musical style probably began in 1966 by Richie Ray and Bobby Cruz. The biggest boogaloo hit of the 1960’s was "Bang Bang" by the Joe Cuba Sextet and it sold over one million copies.

That same year saw the closing of New York City's Palladium Ballroom, when they lost their liquor license. It had been the home of big band mambo for so long and its closing marked the end of mainstream mambo. Thereafter, boogaloo ruled the Latin charts for several years before salsa began to supplant it. Simultaneously, several other rhythmical inventions were becoming popular: the dengue, the jala-jala and the shing-a-ling. All of these were variants of the mambo and cha-cha-cha.

What follows is swing of the hardest sort and bebop makes a surprise return in the groove created by Wagner and Rivera. I listened over and over again and could imagine Monk or Parker or Chick pouring melodies over what was coming from this rhythm section.

A Latin Road Less Traveled features the Cha-cha-chá, a genre of Cuban music. It has been a popular dance music which developed from the danzón in the early 1950's, and became immensely popular throughout Cuba and in New York.

Cha-cha-chá’s creation can be attributed to a single composer, Enrique Jorrín, violinist and songwriter with the Orquesta América. It began in Havana in 1949 but would make its way to New York by 1955. From the outset, cha-cha-chá music had “a symbiotic relationship with the steps that the dancing public created to the new sound.”

"What Jorrín composed, by his own admission, were nothing but creatively modified danzones. The well-known name came into being with the help of the dancers [of the Silver Star Club in Havana], when, in inventing the dance that was coupled to the rhythm, it was discovered that their feet were making a peculiar sound as they grazed the floor on three successive beats: cha-cha-chá, and from this sound was born, by onomatopeia, the name that caused people all around the world to want to move their feet..." (Sanchez-Coll)

Such is the case when listening to A Latin Road Less Traveled as Phoenix Rivera plays on drums what would normally have been provided by the timbales. Throw in a funky “bass drum and snare backbeats (Marlow)” and this is a modern interpretation of what Jorrín must have seen coming. The guiro becomes the unifying factor here as Phoenix Rivera and Ruben Rodriquez are allowed to follow the funk of their own delight.

Listening to this track made me go back and listen to the Yes hit “Owner of a Lonely Heart” and the bass line was right in step with the Chris Squire bass line. Now if Yes had only gotten this rhythm section, something really interesting could have happened.

The difference with samba, however, is the use of different instruments than are usually found in Afro-Cuban music. Again, Marlow describes double bells called Agogo that are tuned in minor thirds. There is a friction drum called the Cuica and shakers (Ganza), triangles “and a small frame drum known as Tamborim.”

The modern samba is basically a 2/4 tempo varied with the use of chorus sung to the accompaniment of palmas and batucada rhythm. Traditionally, the samba is played by strings and various percussion instruments such as the tamborim.

In the 1960’s, Brazil became politically divided under a junta. The musicians of the left followed bossa nova and moved away from the politically conservative samba. In the 1970’s, samba returned to popularity following a rebirth in the late 1960’s.

On Simply Samba, Bobby Sanabria plays all of the traditional samba instruments (beginning with those cool friction drums) while Phoenix Rivera on drums and Ruben Rodriquez’ bass nail down the hard groove. It is Rory Stuart on guitar who adds his own percussive playing of the melody. Like most sambas, this is just fun.

However, add Cristian Rivera’s congas and throw in some blues and you get A Blues-Tinged Samba which is the title of the following track. Congas are not traditionally part of the samba instrumentation but their inclusion creates what Eugene Marlow calls “a lighter feel” because there is no additional percussion. With Frank Wagner back on acoustic bass and Bobby Sanabria on drums, the feel is indeed lighter and Bobby gets to open up more on snare and cymbals. His use of the high-hat is a cool feature that also helps lighten and liven things up.

Gut Bucket Funk+ is a monster funk groove with the free expression of Sanabria, Cristian Rivera and Wagner on electric bass. The pay-off is the adventurous conga solo by Rivera as Sanabria works the drum-kit and cowbell to create an illusion of multiple players or at least multiple arms on Sanabria. This is a penetrating groove that works on the mambo and son-montuno styles. Marlow calls it the “son-mambo-funk-tuno” style.

Mambo is the musical form developed originally in Cuba, with further developments by Cuban musicians in the United States. The word mambo means "conversation with the gods" in Kikongo, a language spoken by Central African slaves taken to Cuba.

In the 1950’s, New York City began to publish articles on an emerging "mambo revolution" in music and dance. Record companies began to use mambo to label the records. Advertisements for mambo dance lessons were in local newspapers. “New York City had made mambo a trans-national popular cultural phenomenon.” As mentioned above, Mambo died when the Palladium Ballroom died.

Phoenix Rivera, Bobby Sanabria, Rory Stuart and Ruben Rodriquez return for A Summer Latin-Funk. Bobby again covers all the traditional bases as he works the cencerro (bongo bell), guiro, timbale, congas, shakers and bongo. Cha-cha-chá, son-montuno and funk are fused into a soulful groove.

The Son style of Latin rhythm is perhaps the most important of them all. Perhaps that is saying too much but its flexibility makes it a greatly adaptive style. It is the perfect bridge between European melodic considerations and the Afro-Cuban rhythmic expression.

Son-montuno was the Son style as expressed among the mountain folk of Cuba and it was Arsenio Rodríguez who is said to have modernized it. He introduced the idea of tiered guajeos (which were Cuban ostinato melodies) and this created an overlapping framework consisting of various contrapuntal parts. This feature of the son's “modernization” has been called a "re-Africanizing" of the music.

That same rhythm section stays on for A Latin Groove which brings back the mambo but with “contemporary NYC attitude.” No mourning the Palladium Ballroom here. Phoenix Rivera adds bits of the Songo style here for good measure.

Out of West Africa brings back the bembe’ rhythm. However, this time it is offered with the normal bembe’ accompaniment of congas in descending order of size, from the segunda down to the caja (a soloist with a stick). Here is where the metal hoe-blade makes its debut on the album. It is played with a stick and is called guataca.

On this track, it is Bobby Sanabria who plays all the positions with the sole addition of a vibraphone-sounding instrument known as the Hand Drum. Small wonder that Eugene Marlow recruits Bobby Sanabria at every opportunity. The performance on this track requires many, many hearings.

Trippingly on the Bass Lines in a roller-coaster of rhythms and tempo shifts. It is Frank Wagner on the acoustic bass again and he does not disappoint. Bobby and Cristian Rivera lay down the opening Bomba Xicá which breaks into a double time swinging bebop before returning to the Bomba Xicá and then easing into a medium tempo bebop rhythm which becomes the dominant feature of the whole track. Dominant, perhaps, but the roller-coaster leaves one breathless. In a cool way.

Simply Samba II brings back that great style that is played in modern fashion with Phoenix Rivera on drums and Ruben Rodriquez on the electric bass. Sanabria is back with the traditional instruments as well as Rory Stuart with the breezy acoustic guitar. It requires no leap of reason to understand why Brazil has some of the most joyful people in the world. With the ubiquitous presence of samba, Carnival should be year-round.

Take a Latin Break ends the album on a blues bent. It is the same rhythm section who are now “swinging over a 12 bar blues form” that changes gears into a “NYC style jazz mambo in 2/3 clave.” Sanabria is on bongo’ and bongo’ bell. There is about a 1.5 second stop before the shift and that moment just hangs there. Talk about antici…pation.

This album is not an oddity or a novelty CD. Maestro Marlow has something in mind.

At first approach, one is compelled to revisit his previous releases and hear them afresh through a new appreciation of the rhythmic elements contained therein. This is sufficient in itself but it cannot be even near the point.

Eugene Marlow is a composer of the highest order but he is also a teacher. Having listened to all of his albums, it can be said with absolute certainty that his aim is never to simply entertain. This is not to say that that entertainment is a base or demeaning goal; it is not.

However, whether it is a renewed hearing of traditional Jewish music redone in modern style or the fusion of Afro-Cuban or Brazilian rhythms with modern jazz, he is teaching something about our world, about our cultures, about us.

In Hitz & Pizz, he teaches us about coming together. His magnificent compositions have always been about bringing diversity into harmony.

The rhythmic patterns of Old Africa meeting New World are for Afro-Cuban and Brazilian music what chord progressions are to European music or modalism is to Eastern music. They are the foundations upon which that particular music is built.

Imagine the happy day when Mongo Santamaria mated the Afro-Cuban groove with the soul of African-American jazz in Herbie Hancock’s Watermelon Man. It was magical, musical alchemy and the world has not been the same since.

This must be Eugene Marlow’s point: we are better when coming together than we are when we remain separated by our own categories. When the delicacy of melody from one place is laid over the powerful rhythms from another place, the whole is truly greater than the sum of the parts.

I will never again be able to hear the Latin rhythms without thinking of the improvised instruments upon which they played: the various sizes of barrels, the two sticks struck together, the empty whiskey barrel and the steel hoe-blade. Lay the sound of a guitar or a bass over them and the alchemy happens.

Maestro Marlow is not simply inviting us to look inside music. He is inviting us to look inside our world and see the beauty of diversity.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed