Paul Ricoeur was born in 1913 in Valence, a small city south of Lyons, France. He was orphaned when mother died (he was 7 months old) and his father was killed at the Battle of Marne in 1915 during the First World War. Paul and his older sister were raised by paternal grandparents who were strict Protestants. His sister, a sickly child from birth, died in 1932 of tuberculosis. She was 22 years old.

As a French citizen, he was obliged to military service in 1935-36. When Germany invaded Poland in September of 1939, Ricoeur was recalled into service during the French mobilization. France and England had declared war on Germany on 1 September 1939 and World War II had begun. The next year he was captured by the Germans and spent the remainder of the war as a prisoner of war in Pomerania. During these five years he helped create a camp "university" and worked out some of his basic philosophical ideas. The camp university was a place of such intellectual acumen that the Vichy French government actually accredited it as a degree-granting institution.

He looked back on the experience without any sense of anger or bitterness. In fact, he referred to it as "extraordinarily fruitful" because it had allowed him time and opportunity to study German philosophy. It is astonishing that he was able to do this in spite of everything that he and France had suffered at the hands of the Germans. Even to the end of Ricoeur's life, Kant, Hegel, Husserl, Heidegger and Jaspers were respected and revered in his thought. In the POW camp, he had translated and written extensively on Husserl's Ideas I. Because of the scarcity of paper, he resorted to writing a nearly microscopic longhand on scraps of paper and in the margins of the book. When he and his fellow-prisoners walked hundreds of miles home at the end of the war, he carried his notes in his backpack. His wife Lysee typed them up for him after his return.

His experiences during this period must have had a direct bearing on his thoughts on goodness. He touched me deeply in his proposal that goodness was not only the answer to evil and it was, of course, the great answer to evil. He had said that as radical as evil may be, it is nothing compared to the depths of goodness. However much goodness may be the answer to evil it is also the answer to meaninglessness.

Ricoeur had studied philosophy at the University of Rennes and in 1934 at the Sorbonne. After the war ended in 1945, Ricoeur began his teaching career and in 1948 accepted a position at the University of Strasbourg while finishing his doctorate at the Sorbonne. In 1956 he was appointed to the chair of general philosophy at the Sorbonne.

For the next decade Ricoeur wrote continuously as a professional philosopher (including Fallible Man and The Symbolism of Evil, both great influences on me). He was an activist against the French war in Algeria and as a reformer of the French university system. In 1967 he left the Sorbonne to assume the administration of a new and experimental university at Nanterre. Here, Ricoeur hoped that he would be able to create a university that followed his educational vision, free from the choking atmosphere of the tradition-bound Sorbonne. Unfortunately, Nanterre became a seat of student and community protest during May, 1968. Ricoeur was ridiculed as an "old clown" and even a tool of the French government. In 1969, he resigned.

For the next two years he taught at Louvain in Belgium before moving to the United States, eventually to the University of Chicago. At Chicago, he succeeded the renowned Paul Tillich as the Chair of the Divinity School and was concurrently appointed to the Department of Philosophy and the Committee on Social Thought. He remained there until his retirement in 1992.

It was in the year 1982 that I was so very honored to meet Paul Ricouer. He was guest lecturing at Vanderbilt University and I was invited to attend a reception held in his honor. I had been so very interested and influenced by his discussion of the frailty of human will in his book Fallible Man. In The Symbolism of Evil, he revealed how we cannot know ourselves directly but only through the symbols that are imparted through memory and literature and mythology. For Ricoeur, the world and scope of philosophy is contained in two questions and two questions only:"Who am I?" and "How should I live?" Ricoeur consistently rejected any claim that the self is immediately transparent to itself or fully master of itself. Self-knowledge only comes through our relation to the world and our life with and among others in that world.

He had never allowed his students or his colleagues to belittle the opinion of another. He had experienced so much heartache and pain in his own life that he would not allow the heartache and pain of another--which reflected in the opinions and beliefs of the other--to be trivialized. A person's views were hard-won and of immense value, even if they radically differed from our own. I am still learning this almost 30 years later.

These questions consumed me then and continue to do so. I was able to speak to him about these very questions. He was wise and gentle. I was young and naive.

"We are always an incomplete project," he said to me. "It is simply our lot and portion in this world. We reach for perfection, for completion, but we will never reach it in this life. The struggle is to continue reaching while we know that it is entirely unattainable."

I mentioned Dietrich Bonhoeffer's poem Who Am I? and he smiled and said, "It is exactly so."

An excerpt of the poem follows:

Who Am I?

By Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Who am I? They often tell me I would step from my cell’s confinement calmly, cheerfully, firmly, like a squire from his country house.Am I then really all that which others tell me, or am I only what I know of myself, restless and longing and sick, struggling for breath, as though hands were compressing my throat, thirsting for words of kindness, trembling with anger at despotisms and petty humiliation, weary and empty at praying, at thinking, faint and ready to say farewell to it all.

Who am I? This or the other? Am I one person today and tomorrow another? Am I both at once? A hypocrite before others, and before myself a contemptibly woebegone weakling?

Who am I? They mock me, these lonely questions of mine. Whoever I am, Thou knowest, O God, I am Thine.

Paul Ricoeur's gentleness and kindness was born of sorrow and pain: the loss of parents and a beloved sister, the horrors of war and being a prisoner of war, being a religious minority in an academic world dominated by the religious majority in France, and the shame and disgrace of being discounted as an old fool.

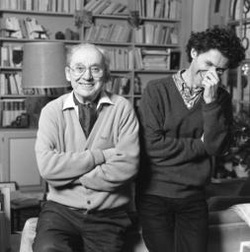

Was it that incompleteness that gave him the strength to move forward? Did the feeling of being a work in progress give birth to his sense of humor and his joy? His sense of humor and his joy struck me deeply. This is why I chose the photo that you see above.

He rose above oppression and loss, pain and ridicule, and blatant opposition. I think his sense of reaching (and not attaining) allowed him to laugh and be kind.

In Oneself as Another he wrote: “there is no self-understanding that is not mediated by signs, symbols, and texts; in the final analysis self-understanding coincides with the interpretation given to these mediating terms.” That was his final analysis of the task of philosophy--the study of "the fulness of language." That is not as trivial as one might take it at first glance because it is here that we find self-understanding. Further, it is where we begin to understand others, as well.

Perhaps this explains my fascination with texts ancient and modern. Mythology and literature give symbol and meaning to our existence and who we are as individuals and communities.

He has asked, "What are the ethical consequences of the ways we conceive of ourselves and others?" Again in Oneself as Another he calls for a "critical solicitude"--a primary concern and protectiveness of others--that is dependent upon a mutual recognition of one another as worthy, capable, and fragile selves.

I think his answer of incompleteness points the way to tolerance toward others and toward ourselves. In our reaching, we should reach toward a tolerance of who we are and, especially, who we are not yet. If we recognize the frailty of one another then it is not only tolerance that is born but a very desirable protectiveness of each other.

As a witness to the horrors of the 20th century, he passionately searched the meaning of justice and love. His great phrase was "Justice proceeds by conceptual reduction; love proceeds by poetic amplification." He saw no conflict between the two, but justice without love is a fetter and can itself become lethal.

This was how Paul Ricoeur thought and lived. He was protective of others--even those who ridiculed and opposed him. He saw his opponents and critics as fragile and in need of protection.

He died peacefully at his home in Châtenay-Malabry, just west of Paris, on May 20, 2005. He was 92 years old. On his passing, The Society of Biblical Literature wrote: "A bright shining star went out." The journal Befindlichkeit wrote: "We will miss you, Paul. Thank you for gracing us with your mind during your illustrious life."

I vividly remember receiving the email notifying me of his passing from The Society of Biblical Literature. I looked at my bookcase where one shelf was loaded with Ricoeur's 20 books. I knew that the fruits of his mind would continue to influence my own mind for the rest of my life. As I reflected, however, it wasn't the books I cherished; it was the spirit of the man. It was his smile.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed